alternative consumption, in other words on countercultural or subcultural practices of clothing consumption, we can analyse with the help of the Levi-straussian concept of “bricolage”.

How do countercultures destabilize the dominant culture through their consumer practices? What are their specificities? How do they differ from the other consumptions?

In his article “Style”, published in the second part of the book Resistance Through Rituals edited by T. Jefferson and S. Hall (1976), John Clarke, a sociologist attached at the time to the famous CCCS of Birmingham (Centre for Contemporary Cultural Studies), the initiator of British Cultural Studies, proposes to make a “partial” and “somewhat eclectic” use of the concept of bricolage, first formulated by the French anthropologist C. Lévi-Strauss in The Savage Mind (1962).

Originally taking place within an opposition between craftsmen and engineers, between on the one hand the ability to perform a large number of diversified tasks in a “closed instrumental universe”, working with “the means of the edge”, and “pre-constrained” elements, and on the other hand an individual acting by “project”, the concept designates in the work of J. Clarke the attitude of subcultures towards clothes and objects.

Indeed, for the author, subcultural bricolage acts through a “re-ordering and re-contextualisation of objects to communicate fresh meanings, within a total system of significances, which already includes prior and sedimented meanings attached to the objects used”. In other words, the subcultural “bricoleur” would effectively draw on a “matrix” of pre-existing objects, before reinterpreting them to bring out a new discourse. Applied to clothing, the individual would borrow from the “fashion” repertoire to subvert the meaning of the pieces she selects. The author illustrates his point with the example of the British Teddy Boys, cheerfully resignifying the “Edwardian Look” by means of bootlace tie or brothel-creepers.

Another sociologist, known for The Meaning of Style published in 1979 (see 2.6. The forms of incorporation), Dick Hebdige will also use the concept of “bricolage”. Quoting J. Clarke, the subcultural bricoleur would target “distinctive rituals of consumption” allowing subcultures to reveal “their ‘secret’ identity and communicates its forbidden meanings”. The fashion discourse thus would be resignified by subcultures within an unconscious process. The author brings these practices closer to Dadaist and Surrealist works. Like the author of a surrealist collage, the “bricoleur” would tend to “juxtapose two apparently incompatible realities on an apparently unsuitable scale”.

we can distinguish between time bricolage, cultural bricolage, and gendered bricolage. The first will extract clothing elements from the past, the second will aim at the juxtaposition of clothes/objects from different cultural fields, while the third will define the “camp” practice of clothing.

Temporal bricolage

“temporal bricolage”, since it is based on a juxtaposition of elements borrowed from outdated/past wardrobes. This consumption pattern is typical of alternative cultures. Beatniks, Hippies, or Punks used the secondhand circuit.

we can also try to understand this phenomenon more broadly by studying part of Second-Hand Cultures (2003), a book written by Nicky Gregson and Louise Crewe, respectively researcher in the Department of Geography at Durham University and Professor of Human Geography at the University of Nottingham.

Reconnecting with the past

In “Transformations: Commodity recovery, Redifinition, Divestment and Re-enchantment”, the authors focus on the role of second-hand objects in the construction of the individual’s identity. Through the consumption of used products, they would first participate in an attempt to faithfully reconstruct the past. The case of Josephine and Ian is exemplary, Josephine only looking for original 1960’s clothes for their quality and cut. The notion of value is no longer as much an economic logic as a cultural one. It is in culture that the value originates, even for the purchase of a 50-cent garment, the alleged authenticity participating directly in a logic of cultural distinction. But this type of purchase also demonstrates an attempt to rebuild an imaginary past. This is the case with Rupert’s relationship with charity shops, perceived as “make accessible earlier constructions of working-class masculinity”.

A negotiation between old and new owners

In addition, the use of second-hand objects or clothing would be linked to “divestment rituals” in opposition to the attempts at revalorization discussed below. In this case, the wearer may feel perfectly free to erase the traces of the old object, the marks of the former owner, or simply to personalize it, and thus “liberate” the meaning of the original object. If I buy a Levi’s 501 in a vintage store, redo it, shorten it, I’m working somewhere to redesign it. We note here the existence of a negotiation between the old and the new holder. The authors also observe that this dialogue is sometimes paradoxically refused, as some buyers try to find the clothes that have been the least worn. In this respect, Val is implementing a whole strategy to notice the newest labels, which are signs of a garment that has been seldom washed and therefore not worn. Janet will refuse to buy jeans because of blood marks in one of the pockets. Basically, there seems to be an impassable barrier for visitors to charity shops. The purchase of underwear is very largely inconceivable for the respondents, followed by “nightwear” or “shoes”. Hence the journey of some buyers like Judy, who started by buying “safe” parts like “outerwear” and gradually moved on to shoes. In addition, these choices may reflect a class relationship. Rupert would never buy underwear, shoes, except if it was “Paul Smith boxers” because probably worn by “a Young trendy person” and not by “an 80-years-old granddad that hasn’t washed”. It is also more reassuring for some to know the path of the garment or its former wearer. This results in a particular relationship to washing, representing a barrier against disease or contamination, i.e. a barrier between the old and the new wearer.

Customisations

Nicky Gregson and Louise Crewe conclude by studying the repairs and customizations that vintage clothing undergoes. For some, transformation is proving to be a way to invest the focus of particular attention. The clothes will be reshaped, the shoulder seams modified, fringes added, a skirt diverted into trousers, the buyer finally revealing himself as a designer capable of recognizing the cultural ability to recognize the potential of a garment before its transformation, often helped however by the intervention of a third party (a tailor for example).

These interventions can also emerge in “spaces of juxtaposition”, with reinvested objects or clothing cohabiting with, for example, new clothes or other periods. This is the example of Lily who never fully dresses in “second-hand for fear of looking “like a tramp”, to prefer a DIY silhouette made by a second-hand dress, a new hat, a customized vintage scarf, and new shoes to produce a clean and contemporary style.

If they are contemporary, the analyses realized by Nicky Gregson and Louise Crewe around second-hand clothes are decisive to determine the propensity for the resignification of old clothes by certain alternative cultures. Thus they seem to echo at the same time attempts to reconnect with a real or fantasized past, or on the contrary practices of juxtaposition of disparate elements that are completely disrespectful of the object’s original time. Let us illustrate the first case with two photographs of the “Fifties” of France in the 1970s taken by Yan Morvan. The band’s propensity to draw from a dressing room straight from 1950s America is a sign of an attempt by them to pay tribute to this imaginary past. Car, teddy jacket, checked flannel shirt, Levi’s jeans are here reintroduced almost literally into a totally anachronistic Parisian environment (Place des Vosges).

On the opposite, the first wave of British Teddy Boys aimed at the juxtaposition of disparate elements. If some of them acquired second-hand “suits” reminiscent of the Edwardian aristocratic dress, they would mix them with other elements borrowed from American rock of the 1950s such as banana hairstyle, knives, or bootlace tie.

Cultural bricolage

French historian Michel de Certeau, famous for his research on religious trends in the 16th and 17th centuries, published the first volume of The Practice of Everyday Life in 1980. A report on research conducted for the DGRST (Délégation générale à la recherche scientifique et technique) from the end of 1974 to 1978, the study focuses on “common and everyday culture as appropriation or re-appropriation”, in other words, on consumption perceived as “the way of practicing”, in order to forge a theory of daily practices.

Following the emergence of British Cultural Studies focused on the study of “popular culture” (R. Hoggart published The Uses of Literacy: Aspects of Working-Class Life with Special References to Publications and Entertainments in 1957, R. Williams Culture and Society: 1780-1950 in 1958, E.P. Thompson The Making of the English Working Class in 1963), the text now allows us to refer to what we will call “cultural crafts”, the juxtaposition of clothing elements borrowed from different cultural fields within the same outfit.

punk

The consumer producer

Chapter 3 “Making Do: Uses and Tactics” of the first part begins with an analogy between the idea of literary styles and “ways of operating”, of reading, living, talking - let’s add here - of dressing. According to De Certeau, the housing methods of Kabyle immigrants in France in the 1970s can be assimilated to “styles”, as they are forced to make an effort to re-appropriate an imposed area. The author therefore proposes to consider the goods consumed as “repertory with which users carry out operations of their own”. He defends the following thesis:

“In reality, a rationalised, expansionist, centralised, spectacular and clamorous production is confronted by an entirely different kind of production, called “consumption” and characterised bu its ruses, its fragmentation (the result of the circumstances), its poaching, its clandestine nature, its tireless but quiet activity, in short by its quasi-invisibility, since it shows itself not in its own products (where would it place them?) but in an art of using those imposed on it.”

Thus, De Certeau shows the difficulty of a “critical” consumption practice based on products imposed on consumers. Instead of a simple passive receiver, the consumer would become a producer of new meanings from an established repertoire of products. He draws a parallel here between these subversion practices and Indian acts of misuse of laws, practices or representations forced during the Spanish colonization. It is therefore impossible to define a a consumer by his own practices, in other words by simple statistical measures, since it is unable to grasp the true use of objects.

The author is gradually moving towards a linguistic approach. If language is assimilated to a “system” and speech to an “act”, then production would be precisely the “system” providing the capital or repertoire, when consumption would approach the “act”, i.e. the way of using this pre-established capital. Basically, the “arts de faire” could be confused with the enunciative model, “use of language and an operation performed on it”, composed of a “realization of the linguistic system through a speech act that actualizes some of its potential”, the “appropriation of language by the speaker”, the establishment of a relationship with a speaker, and an act of locution establishing a “present”.

Consumer tactics

The second part of the chapter introduces a fundamental distinction between strategy and tactics. Defined by a calculation, a specific place, the existence of external targets/threats, by the postulate of a power, the strategic model is rather related to the organization of a company, an army or a scientific institution. Thus it responds to three characteristics: the preponderance of place over time, a control of place by sight (panoptism) and a transformation of the “uncertainties of history into readable spaces”. The “tactics”, as the “arts of the weak”, as arts of deception, are opposed to it. Tactics only act on the outside, according to an external law, without a global project and are reduced to acting “blow by blow”, to poaching.

Thus, the practices of “making” consumers would rather be assimilated to tactics, tricks, poaching, especially necessary since they would be based on “the generalization and expansion of technocratic rationality”, possibly prefiguring a “cybernetic” society. Like the immigrant, the consumer would be forced to operate on an outside field with imposed products. For De Certeau, these tactics could precisely escape the repressive apparatus because of their flexibility and their ability to adapt to change.

The punk practice of clothing

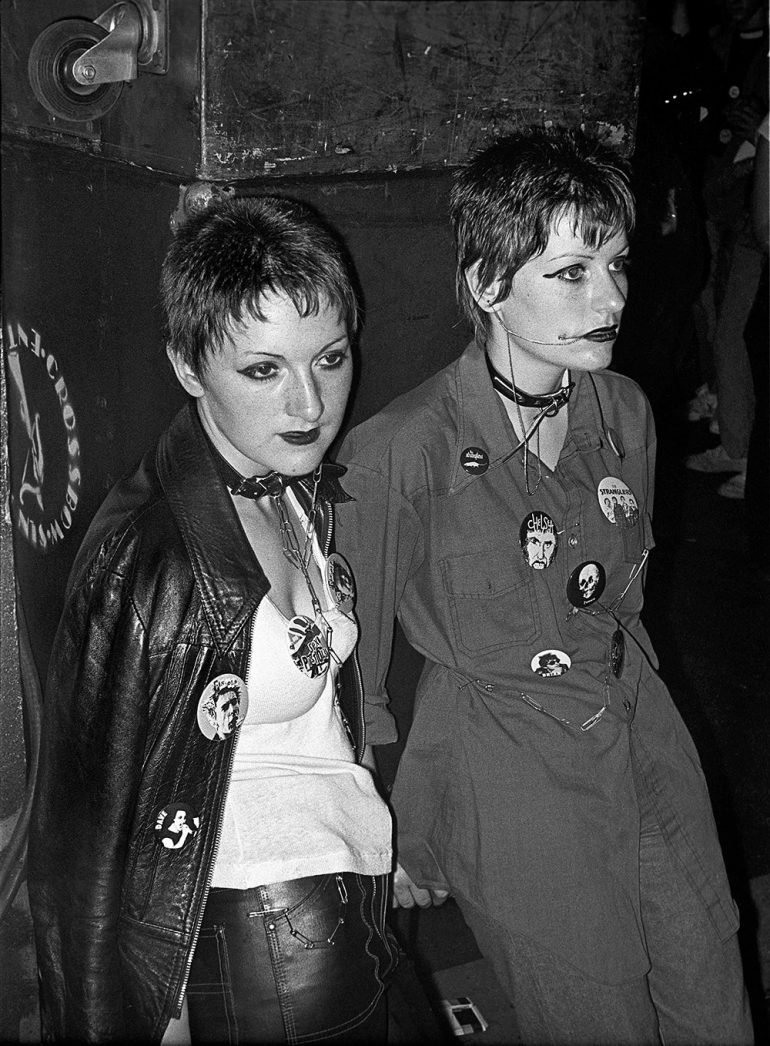

While De Certeau does not dwell on clothing “tactics”, preferring the reading practices (chapter XII), the parallel between counter-cultural clothing practices and poaching seems easy. Let’s illustrate this with a brief study of the elements worn out by the actors of the punk movement in the late 1970s. Similar to popular consumer practices, punk practices have also been built on the diversion of elements borrowed from a consumer repertoire set by the “language producing elites”. Many ordinary everyday objects may have been resignified and emptied of their original meaning. This is precisely what we noticed in the attached photographs. Captured by the famous photographer Derek Ridgers, the first one is emblematic. In particular, dog collars and safety pins are recontextualized in a setting that is completely different from their “regular” practices.

This propensity to reconfigure everyday objects is also present in many photographs taken during the second Mont de Marsan punk festival. Taken by Jean Gaumy, the picture shows us a participant wearing the famous razor blade and a t-shirt made of a can of Coca-Cola, a postcard from the city, but also a banana peel.

Recognizing the consumer’s ability to resignify the products imposed to him, De Certeau was able to provide a major contribution to the understanding of subcultural consumer practices. Let’s now take a look at our latest form of bricolage, the “camp” practice of clothing.

Gendered bricolage

Until now, we have studied two types of counter-hegemonic bricolages, namely temporal and cultural bricolage. Let us now look at a third form of bricolage that we will call “gendered bricolage” or “camp”. To do so, let us first try to clarify our definition of “camp”, which we extract from the reading of Mother Camp, the famous book by American anthropologist Esther Newton.

American cultural anthropologist, Esther Newton is particularly famous for being one of the founders of LGBTQ studies. Based on his thesis in anthropology, her book Mother Camp: Female Impersonators in America, published in 1972, offers an ethnography of the lives of female impersonators and drag queens professional performers in the United States, specifically in the cities of New York, Chicago, New Orleans, Kansas City, San Francisco and Los Angeles. In its chapter 5, entitled “Role Models”, it gives us a definition of the attitude camp.

For Newton, camp cannot be confused with the totality of female impersonators and drag queens, although these two attitudes remain “expressive performing roles”, “both specialize in transformation”. The two approaches are precisely distinguished in that the drag queen only aims at the transition from male to female, thus testifying to an image of a depreciated homosexuality, while the “camp” tends rather towards a “higher synthesis” and would be found at all levels of the homosexual subculture.

Similar to the “soul” of “Negro subculture”, the camp is defined as “a relationship between things, people, activities or qualities, and homosexuality”, in other words as “homosexual taste”, and is summed up in three recurring characteristics: incongruity, theatricality and humor.

- Inconsistency is the first. By aiming at the juxtaposition of opposite elements, the “camp” finally reveals the homosexual experience, itself based on a form of incongruity. Newton retains that the incongruous image of two women or two men in the same bed.

- The “camp” is based, moreover, on a certain form of theatricality. In this respect, an emphatic clothing style is decisive, as a “dramatic form” implying the presence of an actor and an audience, and the perception of “being as playing role”. The author focuses here on the character of Greta Garbo, perceived as “high camp”. By disguising herself in her films as a femme fatale, she finally resembles the way homosexuals dress up as heterosexuals for “playing men”. The author sketches out here the idea of gender performativity, later taken up by Judith Butler in Gender trouble (1990).

- Finally, since its purpose is to make the audience laugh, the third quality of the “camp” is humor taking place in a “system of laughing from its incongruous position instead of crying”.

Esther Newton therefore describes the camp’s productions and performances as “a continuous creative strategy for dealing with the homosexual situation” with a view to “defining a positive homosexual identity”. While all impersonators and homosexuals cannot be defined as such, the camp is a “homosexual wit and clown”, in other words a way of highlighting the “stigmas” of homosexuality to neutralize them.

On the counter-cultural level, this tactic, which we can also define as a form of “counter-hegemonic bricolage”, was used by some groups challenging gender norms in the early 1970’s. Among them, the informal Parisian group on Gazolines is exemplary. Defined as a group of “folles”, it evolved on the fringes of the Homosexual Front of Revolutionary Actions (FHAR) in the early 1970s, and their “main activity consisted in being seen and being scandalous” by noisy staged events. Let us focus on the analysis of some photos of its members, or of people who might be related to it.

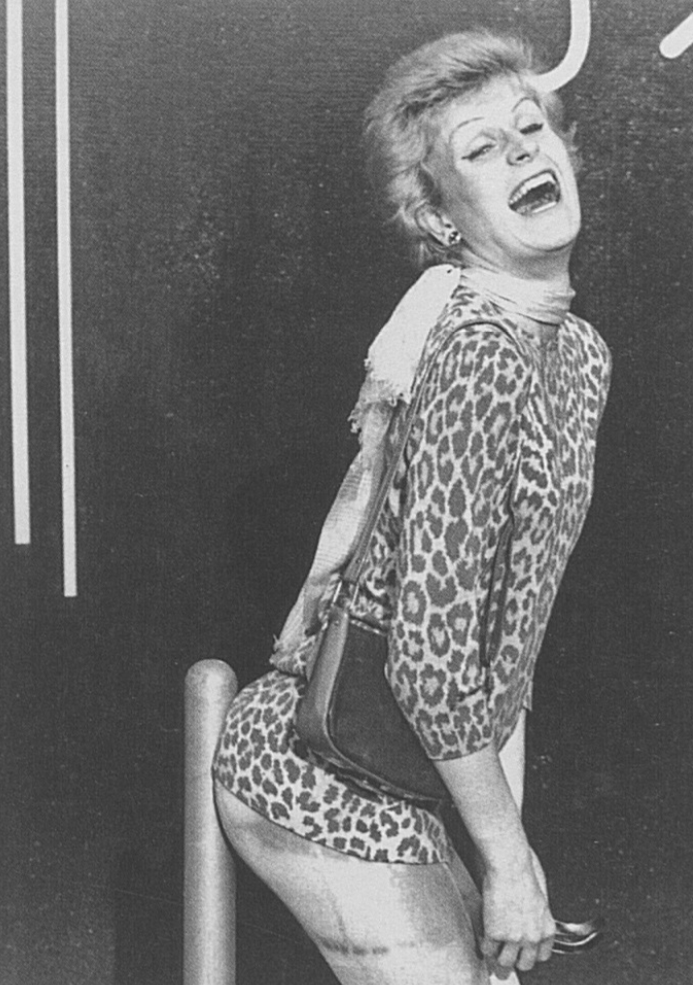

The first image is a photograph of Hélène Hazera, a former member of the informal group. She wears purple and white tie-dye tights, hand-dyed by hand, accompanied by 1940’s silver shoes with Greta Garbo strass, a high panther print, and a vintage handbag and scarf. The acting, the pose, the use of blush and the masculine features started from a blurring of the codes making the reading of the silhouette equivocal.

Another example is given by Dina and Marlène, two Parisian transgenders. Taken in 1977 in the lounge of the Théâtre Montparnasse by the “Belle Journée en perspective” collective, the photograph presents the two protagonists in a provocative pose, arms above, arms below, lower abdomen and bare breasts, visibly drunk. The elements of the wardrobe are significant in more than one way. The two characters seem to enjoy dressing up in products from the Parisian tourist industry. Marlene presents herself with a t-shirt printed with an Eiffel Tower, when Dina matches her friend with a pocket worn on her shoulder on which is similarly visible the Parisian monument. But there is also an interest in Marlène wearing work pants. The cohabitation of tourist effects, work trousers, alongside masculine features and theatrical poses introduce an archetypal equivocal silhouette of the “camp”.

To conclude, the camp defines a third way to subvert the dominant culture through clothing. Through incongruity, theatricality and humor, it ultimately constitutes a formidable strategy of resistance aimed at “destabilizing what emerges from a naturalized norm”.

No comments:

Post a Comment